2020-10-26

License to trill...

I love Baroque music. When I was a grade schooler, I know almost nothing of Baroque music; my favorite vinyl records did not include it. There was a Glenn Gould performance of the Bach D minor keyboard concerto that I really disliked on the flip side of the recording of the Beethoven Second Piano Concerto. I probably wore the grooves out of the Beethoven, but refused to listen to the Bach -- too serious, too dark, too complex.

My Belgian teacher changed that situation practically from our first lesson together. First, Bach's two voice inventions. Then the French suites. Even a few of the preludes and fugues from the Well-Tempered Clavier. By the time I returned to Boston freshman year in high school, I basically played Bach every day. My friends at the NEC Preparatory Division thought I was out of my gourd for signing up to play preludes and fugues in the Saturday noontime recitals in Williams Hall. No one else would... but I loved the music, so I did.

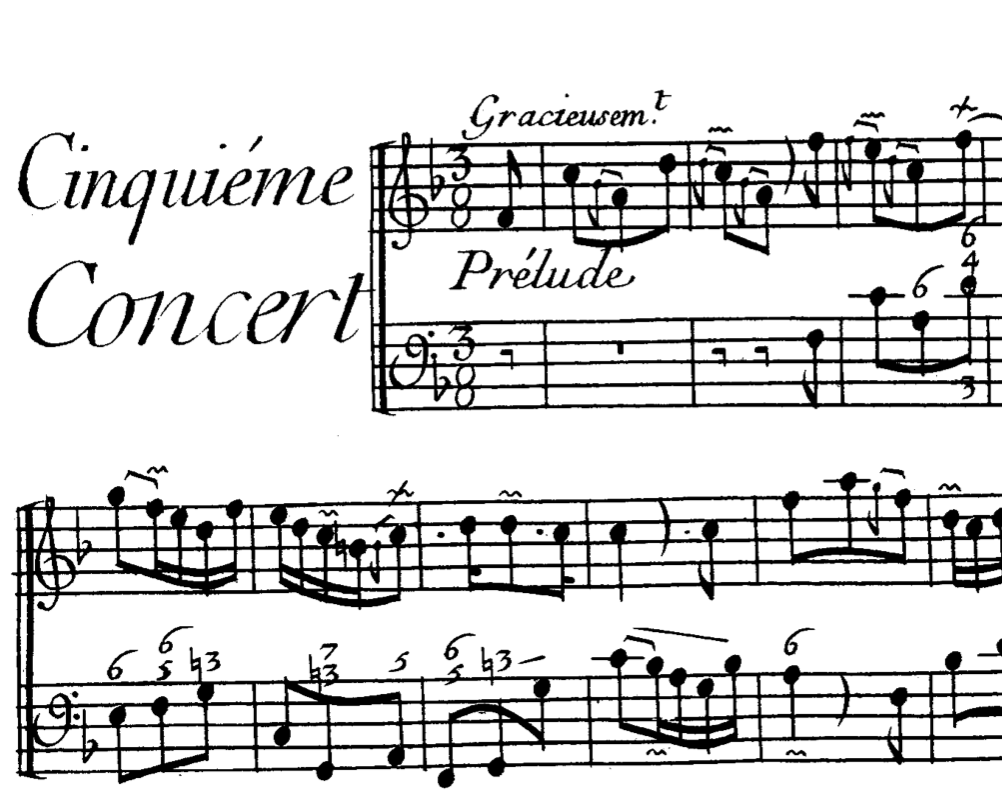

As I learned more and more about Bach and the Baroque and Baroque keyboard practice, I discovered that it was common practice, nay, even >expected<, that the player would "add" ornaments to the score. You could choose! Yes, there were some ground rules, but this was really different from the Classical and Romantic composers, where every note was sacred and you didn't mess with anything. Trills, turns, mordents, doppelschlag, appoggiature... as long as you didn't overdo it, you could add these embellishments to virtually every Baroque score. On the modern piano, the acoustical reasons for the development of some of these ornaments are no longer relevant; but it sure is fun to create the authentic style by adding ornaments to the best of your ability.

Eventually I also came across figured bass as well, and that discovery was just as intriguing. How exactly did a keyboardist create a part from just a bass line and little tiny numbers underneath the staff? It turns out that playing from figured bass requires a solid knowledge of harmony and counterpoint; but if you had done that preparation, the figured-bass short hand was a highly convenient way to notate music quickly and to allow the player to create their own path through the figured-bass map, making up something slightly different every time. Realizing figured bass has always been one of my favorite types of playing. By and large, it was not until the 20th century did "permission" return to the player to "make stuff up" in performance, in contemporary music scores and, of course, in jazz and popular styles.

Ornamentation and figured-bass, hallmarks of the Baroque period, are basically little windows of improvisation in an otherwise notated world of performance. If you want to hear something interesting, check out jazz legend Keith Jarrett's recordings of the Händel keyboard suites. The Baroque aesthetic makes perfect sense to Mr. Jarrett, an outstanding jazz improviser.

So, when you attend your next live Baroque concert, listen closely for those "twiddlies", as my late father-in-law used to call them, in Bach and Händel and Couperin and Vivaldi and Purcell, listen carefully to where they happen... and then go listen to the performance again, also preferably live! A good Baroque player will serve you up a whole new set of solutions. And, like life, nothing will ever be exactly the same way twice.

If you have more questions about this topic, don't hesitate to contact me and we can chat.

K

Previous blog entries